Migration and the Making of the Ancient Greek World (MIGMAG)

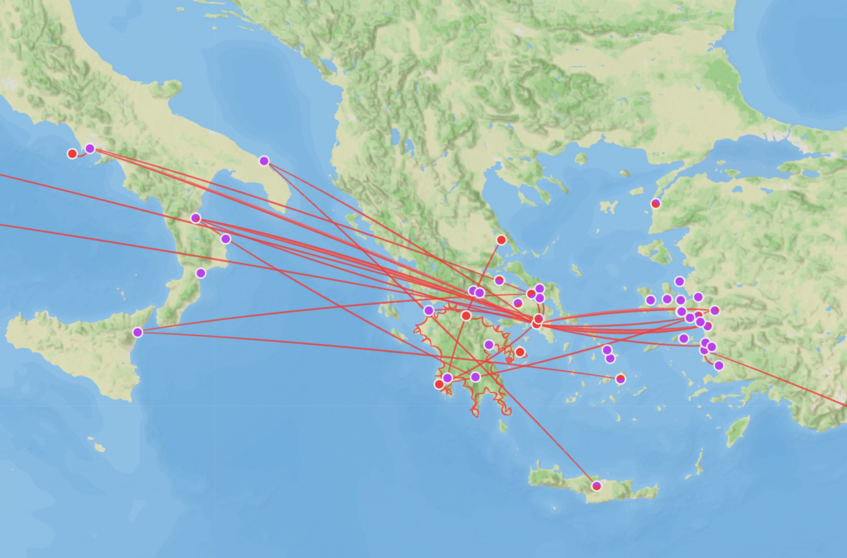

By c.550 BCE, the ancient Greek world was a culturally integrated but geographically dispersed entity, comprising over a thousand autonomous communities scattered across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Migration was evidently crucial in its formation.

What was the nature and the scale of this migration? Who was moving, over why kinds of distances, and how often? The MIGMAG project combines archaeological and historical evidence to explore the human mobilities c.1200-550 BCE that led to the creation of the ancient Greek world as we know it.

Regional migration

Archaeology has established methodologies for investigating long-distance mobilities (both through scientific analyses of ancient DNA, stable isotopes etc.; and also through more traditional analysis of artefacts, styles, and social practices).

Methods for investigating local and regional mobilities are less well established. MIGMAG examines broader demographic patterns across entire regions using landscape archaeology, exploiting new and existing data from archaeological surveys to uncover settlement patterns and environmental change (Work Package 2).

What was the scale of long-distance immigration relative to shorter-distance mobility? Did the establishment of new settlements owe more to an overall increase in regional population (i.e. the arrival of many inter-regional migrants) or to the redistribution of an existing population into a new settlement pattern (i.e. the mobility of intra-regional migrants)? How much mobility was seasonal?

Myth of origin

The formation of collective identities - of communities and states in particular - remains a tense issue into the present day. How did the new communities formed in the period of migration come to define themselves as Greek?

It has often been assumed that ‘Greekness’ of new settlements was the automatic result of communities being founded by Greek people, bringing Greek culture with them when they migrated out of the Greek heartland in the Aegean. Yet Greek migrants settled in some new settlements that never adopted a Greek civic identity (e.g. Sardinia), and both locals and non-Greek migrants were present at many new settlements that did (e.g. Calabria, Ionia).

The simple fact of long-distance migration around the time of foundation cannot, therefore, have been the sole factor determining which communities became Greek. What other factors were at play? Did these factors vary between communities and regions? How and why was a sense of collective Greekness constructed in different places, and how did this change over time? How did community identity develop differently in different parts of the Greek world - whether at its ‘core’ in the Aegean, or in ‘peripheries’ elsewhere?

The MIGMAG project explores the construction of civic identity at new settlements in the generations and centuries after their establishment, examining claims made by and for these settlements about origins, kinship, and identity (Work Package 3). To do this, it will focus on myths of foundation and origin.

Case studies

We are focusing our work on the following regional case studies:

• Western Sardinia

• Calabria (southern Italy)

• Ionia (western Türkiye)

• Rough Cilicia (southern Türkiye)

• East Lokris (central Greece)

Team

PI: Naoíse Mac Sweeney

PDRAs: Jana Mokrišova, Francesco Quondam, Tom Maltas

PhDs: Clara Hansen, Eleni Kopanaki

Administrative Assitants: Bettina Bernegger, Fabiola Heynen

The MIGMAG Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 865644).