Minoisch-mykenische Reliefkunst

Project sponsor: Institute for Classical Archaeology

Project management: ao.Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Fritz Blakolmer

The aim of this habilitation project is to develop an adequate understanding of Minoan-Mycenaean art history on the basis of ancient Aegean sculptures in relief. Relief images on vessels, plaques, interior walls and other image carriers in the materials terracotta, stone, precious metal, faience, wall stucco, ivory, bone and wood form an ideally suited starting point for research into iconography and its mechanisms in the palace cultures of the Bronze Age Aegean. The central questions of this project are, on the one hand, the iconographic and style-critical analysis of the relief works with their complex motifs and an approach to the essential characteristics of Minoan-Mycenaean artistic creation, which is now possible to a much greater extent than a few decades ago. On the other hand, the versatile relief art is better suited than other art genres for reconstructing an art history of the early Aegean period.

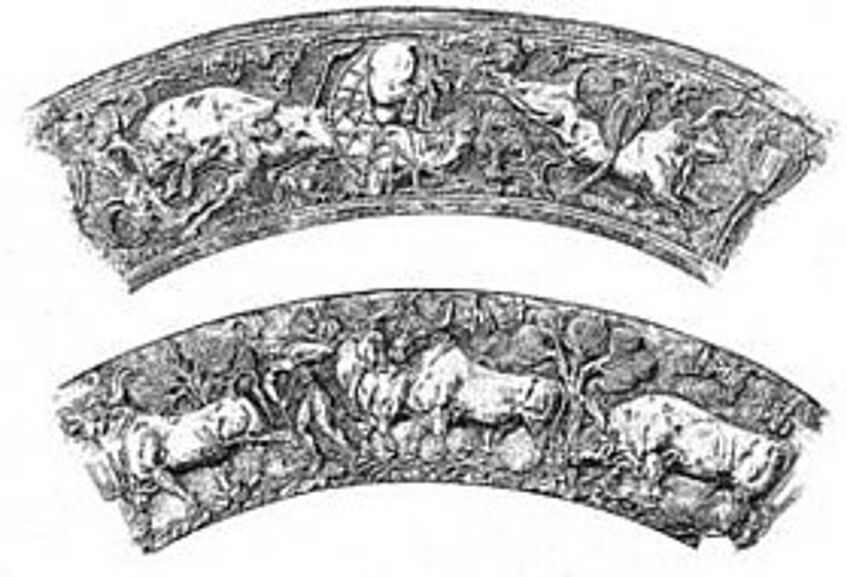

Fig. 1: Gold beakers A and B from Vapheio, wall decoration (after Evans, PM III fig. 123).

Fig. 2: “Reaper vase” from Agia Triada, reconstruction by A. Evans (after Evans, PM II Suppl. Pl. XVII).

The traditional notion of a linear history of the development of artistic style and iconography in the 2nd millennium proves to be valid only to a limited extent. The Minoan pictorial art was already roughly developed in the Middle Minoan, and in part already in the late Old Palace Period of Crete, and reached its zenith in the New Palace Period during advanced MM III and SM I. Again and again we are amazed by the Cretan artists' ability to adapt and their drive for independence in dealing with foreign pictorial ideas. Stylistic versatility, compositional sophistication and narrative qualities (figs. 1-3) are striking characteristics of Minoan relief art that probably go far beyond what has been known to date. Neopalatial-Cretan pictorial concepts can be understood as “classical”, as they form the standardized repertoire for the entire Late Bronze Age, both on Crete and on the Mycenaean mainland. A number of individual observations make it seem likely that the monumental, polychrome stucco reliefs in the palace of Knossos (fig. 4) served as a model and starting point for a pictorial world that spread to all genres of minor art as well as to the whole of Crete and beyond. A study of individual relief works with different pictorial themes suggests that this official palace iconography, its pictorial language and its artistic concepts were disseminated in neo-palatial Crete with the aid of pictorial and motif-type templates in the form of miniature models in relief, which also conveyed the palatial ideology of Knossos to the outside world.

Fig. 3: Silver crater from Shaft Tomb IV in Mycenae, wall unwinding (after I. Mylonas Shear, Tales of Heroes. The Origins of the Homeric Texts [2000] 36 fig. 55).

Fig. 4: Reconstruction of the stucco relief from the “Northern Entrance Passage” of the palace of Knossos.

The struggle for Cretan form and the confrontation with what had once been achieved characterize Aegean art throughout the second half of the 2nd millennium and cast fundamental doubt on the independence and autonomy of “Mycenaean art”. However, even with the term “stylistic decay” we can only do limited justice to the arts on the Greek mainland. Stylistic and motif-historical analyses allow us to disentangle the different strands of tradition, which can be recognized, for example, in the heterogeneous spectrum of precious objects with pictorial decoration from the shaft tombs of Mycenae. Many more iconographically designed objects (fig. 3) can be assigned to the Minoan tradition and defined as imports from Crete than was previously assumed in research. However, an autochthonous Helladic style also becomes more tangible in many shaft tomb-period sculptures, which were already oriented towards Cretan motifs to varying degrees in statu nascendi and adapted Minoan motifs laboriously, improvisationally and individually. The process of “Minoization” is still unmistakable in relief art on the Mycenaean mainland in SH IIB-IIIA1, and examples of small-scale art imported from Crete may have played an essential role in the creation of mainland sculptures. Neopalatial-Cretan motifs and stylistic forms are always imitated and combined with one another. This often manifests itself in an un-Minoan overload of traditional, partly reinterpreted or misunderstood Cretan motifs (fig. 5). This tendency continued into the Mycenaean palace period, and in some cases we gain the impression that the pictorial art was now deliberately intended to convey an official Mycenaean return to the former “splendor of Crete” (fig. 6). Nevertheless, the winner in this creative debate is always Crete. Until the end of the Bronze Age, Mycenaean relief art shows no sign of emancipation or separation from the models of Neo-Palatial Crete, nor of the development of an independent tradition. In the artistic sector, “Mycenaean” always meant “wanting to appear Minoan”.

Fig. 5: Mycenaean gold cup from Dendra (after A. W. Persson, The Royal Tombs at Dendra near Midea [1931] frontispiece).

Fig. 6: Mycenaean ivory plaque from the “House of Sphinxes” in Mycenae (after A. J. B. Wace, BSA 49, 1954, pl. 38 c.).

Projektergebnisse:

- F. Blakolmer, Zu Ikonographie und Charakter des frühägäischen Stuckreliefs, Internet-Zeitschrift Forum Archaeologiae - Zeitschrift für klassische Archäologie (http://farch.net) 11, Juni 1999.

- F. Blakolmer, Das minoisch-mykenische Stuckrelief. Zur Definition einer palatialen Kunstgattung der ägäischen Bronzezeit, in: F. Blakolmer – H. D. Szemethy (Hrsg.), Akten des 8. Österreichischen Archäologentages vom 23. bis 25. April 1999 am Institut für Klassische Archäologie der Universität Wien, Wiener Forschungen zur Archäologie 4 (Wien 2001) 19–36.

- F. Blakolmer, Zum Fragment eines minoischen Stuckreliefkopfes aus Knossos, ÖJh 71, 2002, 11–19.

- F. Blakolmer, The Minoan Stucco Relief: A Palatial Art Form in Context, in: Acts of the 9th International Congress of Cretan Studies, Elounda, 1-6 October 2001, I 3 (Irakleio 2006) 9–25.

- F. Blakolmer, Vom Wandrelief in die Kleinkunst: Transformationen des Stierbildes in der minoisch-mykenischen Reliefkunst, in: F. Lang – C. Reinholdt – J. Weilhartner (Hrsg.), STEPHANOS ARISTEIOS. Archäologische Forschungen zwischen Nil und Istros. Festschrift für Stefan Hiller zum 65. Geburtstag (Wien 2007) 31–47.

- F. Blakolmer, The Silver Battle Krater from Shaft Grave IV at Mycenae: Evidence of fighting "heroes" on Minoan palace walls at Knossos?, in: R. Laffineur – S. P. Morris (Hrsg.), EPOS. Reconsidering Greek Epic and Aegean Bronze Age Archaeology. Proceedings of the 11th International Aegean Conference, Los Angeles, UCLA - The J. Paul Getty Villa, 20-23 April 2006, Aegaeum 28 (Liège – Austin 2007) 213–224.

- F. Blakolmer, Die "Schnittervase" von Agia Triada. Zu Narrativität, Mimik und Prototypen in der minoischen Bildkunst, Creta Antica 8, 2007, 201–242.

- F. Blakolmer, Der autochthone Stil der Schachtgräberperiode im bronzezeitlichen Griechenland als Zeugnis für eine mittelhelladische Bildkunst, ÖJh 76, 2007, 65–88.

- F. Blakolmer, Small is beautiful. The significance of Aegean glyptic for the study of wall paintings, relief frescoes and minor relief arts, in: W. Müller (Hrsg.), Die Bedeutung der minoischen und mykenischen Glyptik. VI. Internationales Siegel-Symposium aus Anlass des 50 jährigen Bestehens des CMS, Marburg, 9.–12. Oktober 2008, CMS Beih. 8 (Berlin 2010) 91–108.

- F. Blakolmer, The iconography of the Shaft Grave period as evidence for a Middle Helladic tradition of figurative arts?, in: A. Philippa-Touchais – G. Touchais – S. Voutsaki – J. Wright (Hrsg.), MESOHELLADIKA. La Grèce continentale au Bronze Moyen. Actes du colloque international organisé par l’École française d’Athènes, en collaboration avec l’American School of Classical Studies at Athens et le Netherlands Institute in Athens, Athènes, 8-12 mars 2006, BCH Suppl. 52 (Athen 2010) 509–519.

- F. Blakolmer, Der verlassene Stier. Zu Musterbüchern in der Bildkunst des minoischen Kreta, in: ETEOKPHTIKA 1, 2011 (http://www.eteokriti.at/publikationen/eteokphtika/ausgabe-1-2011/).

- F. Blakolmer, Creto-Minoan art abroad or Mycenaean imitation? The case of the bull reliefs from the Treasury of Atreus at Mycenae, in: 10th International Cretological Congress, Khania, 1-8 October 2006, I 3 (Chania 2011) 461–482.

- F. Blakolmer, Image and architecture: reflections of mural iconography in seal images and other art forms of Minoan Crete, in: U. Günkel-Maschek – D. Panagiotopoulos (Hrsg.), Minoan Realities. Theory-based Approaches to Images and Built Spaces as Indicators of Minoan Social Structures, International Workshop am Institut für Altertumswissenschaften, Seminar für Klassische Archäologie, Universität Heidelberg, 16. November 2009, Aegis (Louvain) (im Druck).

Tel.: 0043-1-4277-40620

E-Mail: Fritz.Blakolmer@univie.ac.at