Reception of Minoan-Mycenaean art in the 20th century

Project sponsor: Institute for Classical Archaeology

Project management: ao.Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Fritz Blakolmer

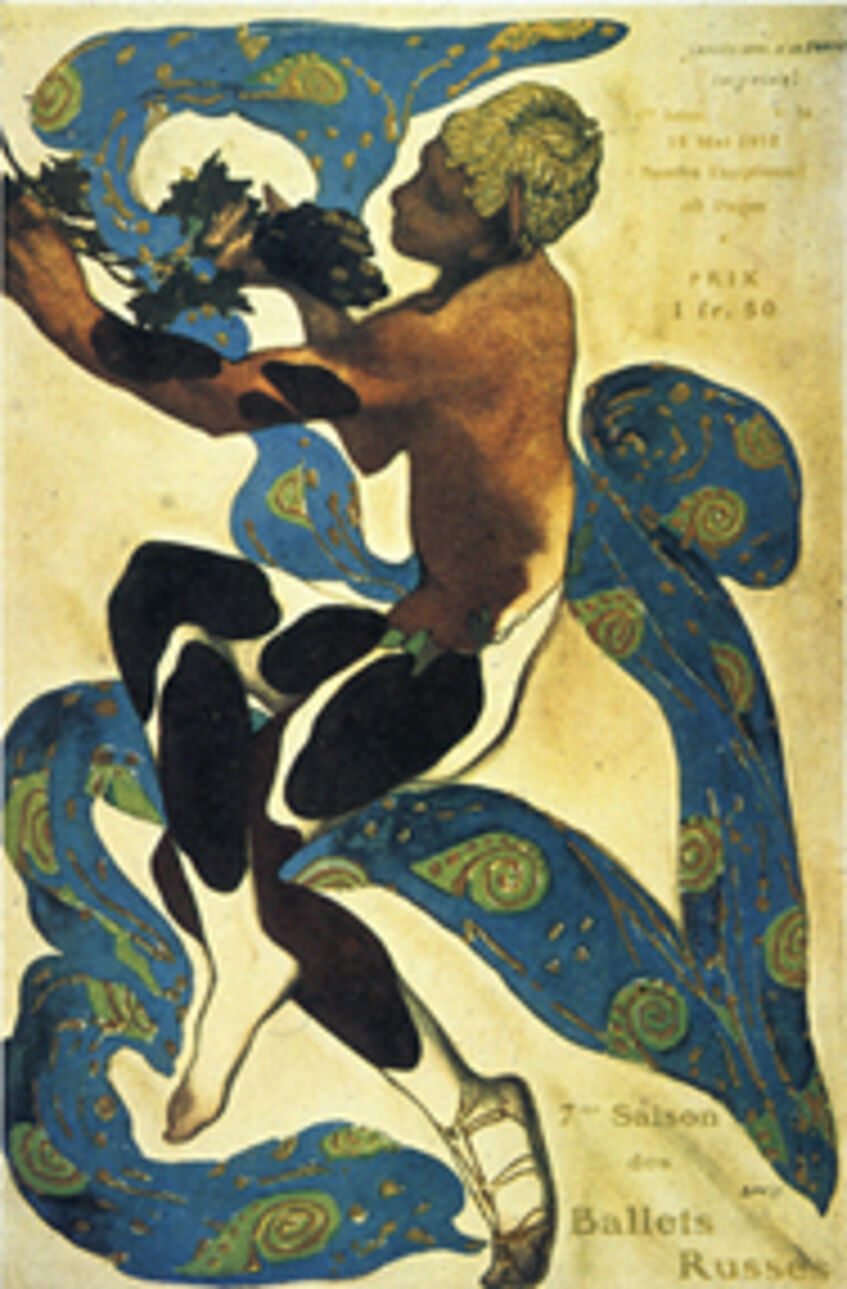

Fig. 1: Leon N. Bakst, set design for Phaidra (after A. Farnoux, Archaiologia & Technes, 86, March 2003, 39 Fig. 9).

The monuments of the Bronze Age Aegean uncovered by Heinrich Schliemann from 1870 and by Arthur Evans and others from 1900 onwards coincided with the intellectually turbulent and artistically innovative decades of the European “fin de siècle”, when neo-primitivism and a revolting liberation movement in art flourished in terms of form, style and content. This coincidence in time between the discovery of a Mannerist-style art of the early Aegean “Homo ludens”, characterized by floral landscapes and spiral ornamentation, and an artistic expression of the European avant-garde based on similar preferences has often led researchers to suspect a causal connection.

On the one hand, numerous pictorial works and interior designs of Art Nouveau could have been influenced by monuments of the Minoan-Mycenaean world; on the other hand, reconstructions of Cretan-Minoan architecture as well as wall paintings and, not least, forgeries could have been influenced by contemporary artistic tendencies of the “Modern Style”.

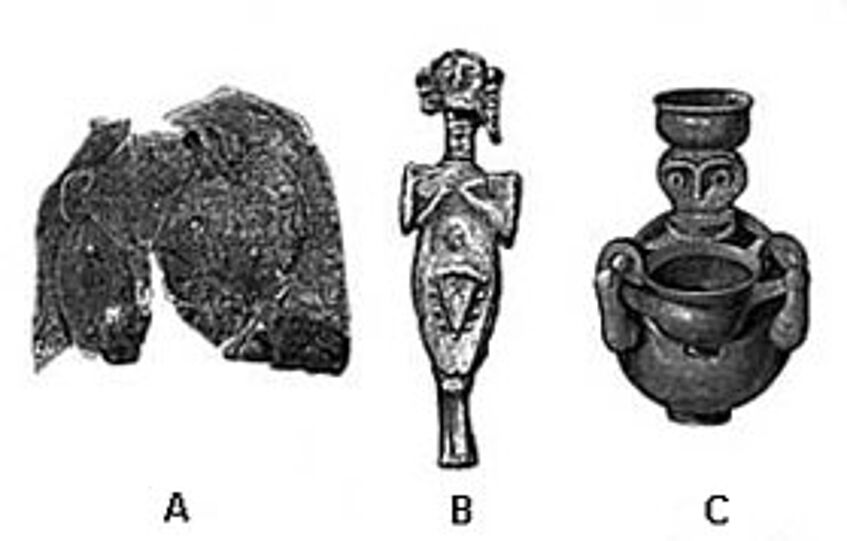

There are numerous examples of the reception of early Aegean spiral ornamentation and the striking Minoan column form (Fig. 1) in Art Nouveau, Modern Style and Art Nouveau paintings. Clearly and in accordance with the artist's statements, the young Oskar Kokoschka used finds from Troy and Mycenae as a source of inspiration for his prints and above all portraits, whose “frozen features of a skull ... with their soulful tattoos” (J. Hodin) are vividly reminiscent of the shimmering, dented gold masks from Mycenae in Schliemann's publications (figs. 2-3). The portrait of the Tietze couple (fig. 4), which Kokoschka expressly described as “Mycenaean”, is also revealing: If “the doctor” resembles a “lion” - according to Kokoschka, obviously in reference to the lion's head rhyton from Mycenae (fig. 5 a) - it is no coincidence that he dubbed “the madam” an “owl”; anthropomorphic objects found in Troy (fig. 5 b-c) also confirm this impression and were already wrongly defined by Schliemann as “owl-shaped”.

Fig. 2: Kokoschka. The Paintings 1906-1929 [1995] 31, no. 52).

Fig. 3: Gold mask from Shaft Tomb IV, Mycenae (after C. Schuchhardt, Schliemanns Ausgrabungen [1890] 264 fig. 234).

But what were the reasons for this “cretomania” in European Art Nouveau? An essential aspect of the artistic connection to Minoan-Mycenaean images, motifs and stylistic traditions in the first decades of the 20th century was probably their non-classical appearance, as early Aegean art has characteristics and qualities that stand in marked contrast to those of classical antiquity. In the avant-garde artists' conflict with traditionalist classicism, the unbridled imagery of the ancient Aegean, the “art of restlessness” and the “eccentric ornamentation” of this “sunken fairy-tale world”, came in very handy. These are not peculiar exceptions that could be taken up here, but the typical early Aegean formal language converged in many respects with the nature and intentions of the artistic and intellectual avant-garde of the “fin de siècle”.

Fig. 4: Oskar Kokoschka, double portrait of Hans and Erika Tietze, 1909 (after Winkler - Erling op. cit. 19, no. 35).

Fig. 5 a: Golden lion's head rhyton from Shaft Tomb IV in Mycenae (after C. Schuchhardt, Schliemanns Ausgrabungen [1890] 279 fig. 249); b: Lead idol from Troia (after Schuchhardt op. cit. 88 fig. 63); c: Anthropomorphic vessel from Troia (after Perrot - Chipiez VI [1894] 653 fig. 295).

To this day, the supposed lack of rules and irrationality in the image are attributes of the Cretan-Minoan idea of form in particular, whose reception at the time of the “fin de siècle” had a lot to do with a longing for otherness and originality, for a return to the “magic” and the “enchanting spectacle of a more beautiful world”, according to the archaeologist Valentin Müller, and presented an Aegean sphere of contrast to Greek Classicism as well as to European Classicism. Instead of having to look to one's “own” early period, be it Celtic, Germanic or Avar, or to foreign continents such as Japan, Oceania, Africa or Latin America, this longing for a “primitivism” could also be conveyed from the beginning of the 20th century with the help of a fresh culture of the distant pre-classical past on the edge of the European continent, unencumbered by the traditions of research history, and this on the soil of Greece. A foreign, ancient “counter-world” gained contours which - in retrospect - did not always do it justice, but which nevertheless played a welcome role in the scholarly world and the public as well as in avant-garde art.

As convincing as many iconographic correspondences and as captivating as borrowings, particularly from the Minoan-Mycenaean ornamental language, may appear in works of Art Nouveau, many examples of a reception of ancient Aegean art suspected in archaeology and art history research are likely to be merely coincidences, as the date of origin of many of these works of modern art clearly predates the date of discovery of the presumed Aegean parallels. Added to this is the fact that the essential characteristics of the “Modern Style” were already clearly developed before the discovery of the relevant ancient Aegean works of art, so that a decisive formative function of the history of discovery and research of the Minoan-Mycenaean civilization in the development process of Art Nouveau can be ruled out.

Fig. 6: Leon N. Bakst, cover of the program booklet Debussy, Nachmittag eines Fauns, 1912 (after H. H. Hofstätter, Jugendstil. Druckkunst [1968] fig. p. 279).

Fig. 7: “Monkey fresco” from Akrotiri, Thera, recovered in 1970 (after N. Marinatos, Art and Religion in Thera [1984] 115 fig. 81).

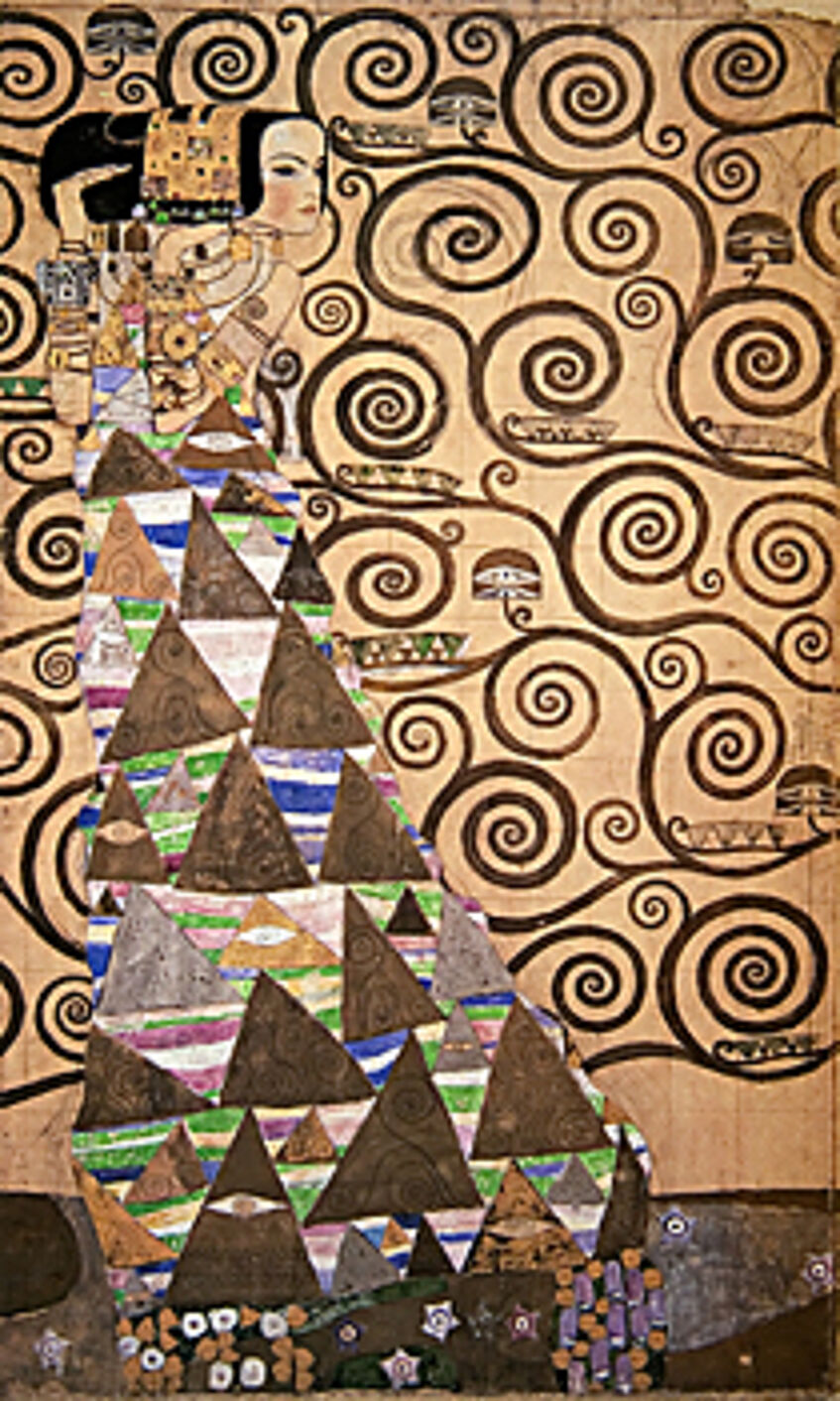

The tectonic, ornamentally structured background design of Art Nouveau paintings and products of the decorative arts comes astonishingly close to Minoan wall paintings. Looking at the playful faun in front of an ornamentally segmented background in the graphic by Leon N. Bakst (Fig. 6) from 1912, for example, one might think that the monkeys in a colourful landscape in a Cycladic mural from Akrotiri on Thera (Fig. 7), which was only uncovered in 1970, are a clear model. This could not have been the case, just as Gustav Klimt could not have used the late Minoan cup with helmet and shield motif in front of tectonic “spiral wallpaper” from Knossos (Fig. 9) for his spiral ground in the frieze of the Palais Stoclet in Brussels (Fig. 8), which was only published in 1914. The list of such “coincidences” or “impossible receptions” could be continued endlessly and leaves us searching for other explanations for some of the often astonishing and diverse similarities at the level of artistic “will to form” in the pictorial language of the Aegean Bronze Age and Art Nouveau. It would be legitimate to speak of mere coincidence here, but a cultural-historical explanatory model that takes into account the character of civilizational upheaval, an emancipation from outdated stereotypes, could prove just as valid for the obvious correspondences in artistic expression. If the artists of the avant-garde sought new paths during the “fin de siècle” that consciously contradicted the classicist traditions, the early Aegean pictorial language, especially in neo-palatial Crete, is characterized by an emancipation from the Eastern Mediterranean “straightforwardness” and also ushered in a kind of new era.

Fig. 8: Gustav Klimt, work model for the frieze in the Palais Stoclet, 1905-1910 (detail) (after S. Partsch, Klimt. Leben und Werk [n.d.] 189 fig. 61).

Fig. 9: Polychrome handle cup from Isopata, Crete (after A. Evans, Archaeologia 65, 1914, 26 fig. 37 a-b).

Projektergebnisse:

- F. Blakolmer, Die Wiederentdeckung der minoisch-mykenischen Kunst zur Zeit des Fin de siècle. Zu Rezeption und 'Koinzidenz' im Jugendstil, KölnJb 32, 1999, 477–502.

- F. Blakolmer, Überlegungen zur Rezeption minoisch-mykenischer Kunst zur Zeit des Jugendstils, in: Akten der Tagung: Antike Tradition in der mitteleuropäischen Architektur der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, Prag und Litomyl, 10.–15. November 1998, Studia Hercynia 3 (Prag 1999) 133–141.

- F. Blakolmer, Zum Kenntnisstand der frühägäischen Denkmäler zur Zeit des 'Fin de siècle', in: J. Bouzek u.a. (Hrsg.), Akten der Tagung "Antike Tradition in der Architektur und anderen Künsten um 1900", Studia Hercynia 8 (Prag 2004) 4–19.

- F. Blakolmer, Altägäische Kunst, Primitivismus und Moderne: Aspekte künstlerischer Rezeption und Verwandtschaft, in: J. Bouzek u.a. (Hrsg.), Akten der Tagung "Antike Tradition in der Architektur und anderen Künsten um 1900", Studia Hercynia 8 (Prag 2004) 45–58.

- F. Blakolmer, The Arts of Bronze Age Crete and the European Modern Style: Reflecting and Shaping Different Identities, in: Y. Hamilakis – N. Momigliano (Hrsg.), Archaeology and European Modernity: Producing and Consuming the 'Minoans', Creta Antica 7 (Catania 2006) 219–240.

- F. Blakolmer, "Der sinnliche Reiz der Zerstörung". Fritz Wotruba und die antike Plastik, in: A. Husslein-Arco – A. Weidinger (Hrsg.), Fritz Wotruba. Einfachheit und Harmonie. Skulpturen und Zeichnungen aus der Zeit von 1927–1949, Ausstellungskatalog Belvedere Wien, 24. April – 23. Juli 2007 (Wien 2007) 23–30.

- F. Blakolmer – J. Bouzek, Bericht über das Symposium 'Zeit-Brücken: Art Déco, Kubismus, Neoklassizismus und Antike' in Prag 2008, Studia Hercynia 12, 2008, 101 f.

- F. Blakolmer, Die "Rekonstitution" des 'Palace of Minos' in Knossos im Spiegel des Art Déco. Und warum Evans recht hatte, Studia Hercynia 12, 2008, 103–116.

- F. Blakolmer, Die Erforschung der Altägäis in den 20er und 30er Jahren des 20. Jahrhunderts, in: J. Bouzek u. a. (Hrsg.), Akten des Kolloquiums "Zeitbrücken – Art Déco, Kubismus, Neoklassizismus und die Antike", April 2008 in Prag, Studia Hercynia 13 (Prag 2009) 5–18.

- F. Blakolmer, Die Formensprache des Art Déco und die minoisch-mykenische Welt, in: J. Bouzek u. a. (Hrsg.), Akten des Kolloquiums "Zeitbrücken – Art Déco, Kubismus, Neoklassizismus und die Antike", April 2008 in Prag, Studia Hercynia 13 (Prag 2009) 23–36.

- F. Blakolmer, Oi technes tis Kritis tin Epochi tou Chalkou kai to evropaiko Moderno stil: apeikasmata kai diamorfosi diaforetikon taftotiton, in: G. Chamilakis – N. Momigliano (Hrsg.), Archaiologia kai evropaiki neoterikotita paragontas tous «Minoites» (Athen 2010) 301–329 (in Griechisch).

- F. Blakolmer, Images and perceptions of the Lion Gate relief at Mycenae during the 19th century, in: F. Buscemi (Hrsg.), Cogitata tradere posteris. The Representation of Ancient Architecture in the XIXth Century. Proceedings of the International Conference The drawing of ancient monuments in the XIXth century. Between technics and ideology (Catania, 25th November 2009) (Rom 2010) 49–66.

- F. Blakolmer, Antikenrezeption vom Klassizismus bis zum Art Déco: Ägypten, Altägäis und Europa, in: A. Junová Macková – P. Onderka (Hrsg.), Crossroads of Egyptology. The Worlds of Jaroslav Cerný, Conference Egypt & Austria VI, Prague, 21st–24th September 2009 (Prag 2010) 133–152.

- F. Blakolmer, "Das älteste Denkmal europäischer Skulptur". Das Löwentor von Mykene in Illustrationen des 19. Jahrhunderts, Internet-Zeitschrift Forum Archaeologiae - Zeitschrift für klassische Archäologie (http://farch.net) 54/XII/2010, Dezember 2010.

- F. Blakolmer, Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Nuraghic, Gothic or Classical Greek? The Understanding of Aegean Bronze Age Monuments in the 18th-19th Centuries, in: T. Kajfez – M. Frelih – I. Lazar (Hrsg.), Meetingpoint Egypt. Conference Egypt & Austria VIII, Ljubljana, 25th - 28th September 2012 (in Druckvorbereitung).

Tel.: 0043-1-4277-40620

E-Mail: Fritz.Blakolmer@univie.ac.at